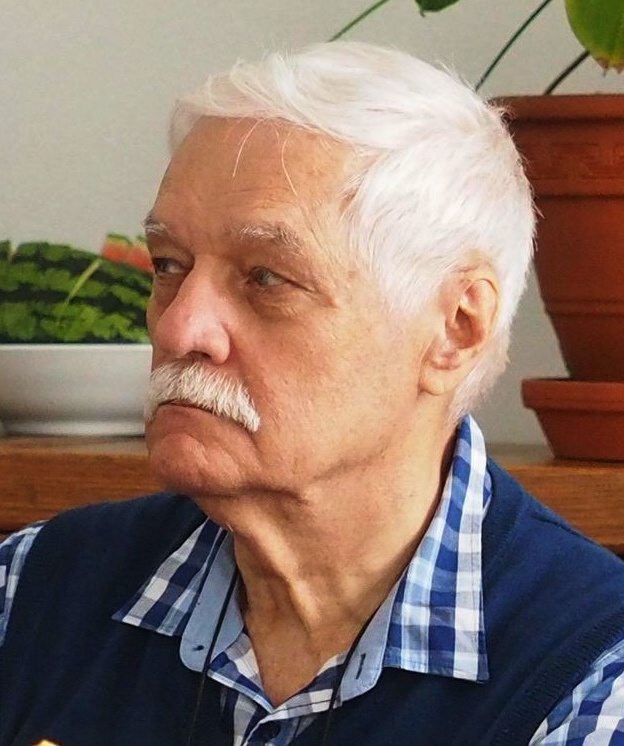

JUDr. Jaroslav Košťál,

CSc., who was for

several years head of audience research at Czech Radio,

joined GEAR in 1987 when the meeting was in

Budapest. He remained in GEAR until he left Czech Radio in the

early 1990s to set up his own research company which was

then later taken over by one of the big companies, probably

TNS. He

retired from research in the early 2000s and kept in touch. He

visited the Myttons several times, and Janet and Graham

enjoyed his hospitality also often Prague, especially

going to Prague’s several opera performances. Jaroslav stayed

with Graham last in 2016 and of course he came to GEAR

Plus in Prague in 2017.

Jaroslav

and Graham had met at the 1984 IAMCR conference in Prague.

Graham was invited by Jaroslav to go and see his department at

Czech Radio. Being in a tightly controlled and intrusive

communist regime and with a communist apparatchik in the

office with him there was a limit to what he was able or free

to say. After an hour or so Graham got up to leave and

Jaroslav accompanied him out of the building on his way to the

Metro. As soon they were

in the street, Jaroslav said “Now we can talk.” Both were good

friends for the next 34 years.

Between

1984 and 1989 Jaroslav rarely felt able to contact Graham,

except when he went on holiday somewhere else in another

Warsaw Pact country. Then he would send a postcard. Then in

1989 he telephoned to say with some understandable enthusiasm

that “It is all over!”

We

all will miss him. Jaroslv died at 75. He had

three children, two grandchildren and two great

grandchildren.

by

Graham Mytton

Jaroslav's funeral

ceremony was very dignified,

attended by cca 50 people. Besides family members, relatives

and former

colleagues from the field of research, there were also

representatives from the

Czech Academy of Sciences, one member presented a moving

mourning speech. Vlasta I expressed her sympathy to the

family on behalf

of the European researchers.

Jaroslav

Kostal: My GEAR

Berne 1990

Tony Fahy,

Tamás Szecskö

Adam Levendel

Graham Mytton

Peter Menneer

(Miloš Řehák – 1967-8, Josef Čamský 1969),

dossier, testimonial

Some forty years ago as a young system analyst I

started my career in Czech Radio. It was during the turbulent

times following the Soviet invasion of 1968. At that time, new

positions were created while many working places and even

whole institutes had been abolished.

The Czech Radio planned to buy a large computer

and our department’s task was to prepare an agenda for it.

When Radio Prague International started to work on enquette of

its foreign audience my boss remembered my sociological

background and sent me to help them. That was the occasion of

my first contact with Graham Mytton who very kindly forwarded

to me several questionnaires that had been filled in by

listeners who accidentally sent them to the B.B.C. instead of

to Radio Prague.

I would like to point out the specific conditions

of our work under the

Communist rule. Anybody who wanted to publish anything

(even a student diploma thesis or a non-ideological text of

methodological nature), had to first “launch a fog”, i.e., to

start the article by several quotations of Soviet authors.

This was a rule across most of the Eastern and Central

European region most of the time. (Hungary and Poland during

the period of thawing in late 1980s and the Gorbachev era

began to be exceptions: I remember some Western participants

of the IAMCAR conference in Prague 1984 asked me about the

“fogging practice” politely with barely hidden disapproval.)

Generally, people who were not ideologically

acceptable to the Communist leaders, or people who emigrated

to the West, were not supposed to be quoted or even mentioned.

Still, one could smuggle them into the text if you flew under

the censors’ radar. So you could publish about a music

theoretician and sound questionnaire pioneer Prof. Karbusický,

who had been working for private radio stations in Western

Germany in those times. Or

you could even publish something about Czech audience research

pioneer Josef Ehrlich, despite the fact that he was

politically persecuted and probably ended up in a communist

jail as a prisoner of conscience in the 1950’s. Fortunately,

there were no web or computer supports to aid censors’ work

and they missed everything that was above their level of

knowledge.

For instance, Jiří Lederer, one of the most

prominent reformer journalists, had been the head of the Czech

Radio Audience Research during the optimistic era of 1962-1967

until he went over to a newly founded magazine Reporter. He

had a close relationship with Polish journalists and Polish

audience research specialists, also thanks to his Polish wife.

In 1972-1973 and again in 1977-1980 he was incarcerated

because of his writings against the Soviet occupation and the

spreading of so called “ideological diversion,” i.e.,

divergent and therefore unauthorized books and magazines.

After his release Lederer emigrated and shortly lived in

Birnbach in Western Germany, where he soon passed away in

1983. Most of this I learned much later, after the democratic

change of 1989.

In 1976 I became a manager of the Audience

research department. I shall explain later on how it happened.

In my new position I started to actively inquire who was who

in the audience research departments in Eastern Germany,

Bulgaria and the Soviet Union and how they did their research.

Obviously, under Soviets, science was under the dictate of

ideology. Naturally pure data collection & commentary

including audience research less so. For many decent persons,

audience research was a good option, though it also brought

along a Hamlet like question, which had been accompanied by

ever-repeating abolition from above.

The same rule was apparent on the international

scale: for instance, there was a great difference between

practically no audience research in Bulgarian Radio on the one

hand and sophisticated empirical approach of our Eastern

German colleagues on the other. The Russians practiced good

professional work but almost in a clandestine manner. I found

their research unit after extensive asking: in a battered old

ex-tzarist palace far from the Radio and TV headquarters.

Hungary and Poland did not have a good reputation in the

ideological sense and thus the Czech Radio management would

not let me go to learn there. As a matter of fact, I studied

sociology that was reintroduced to universities in 1966, and

in the absence of Czech materials obtained what was

needed from books by Zygmund Bauman, Jan Sczepanski and other

Polish experts. Poland was the only country under the Soviet

rule, which never interrupted the practice of this “bourgeois

quasi-science” as it was labelled by Lenin.

I also tried to go to the roots and discovered,

that the founding father of the regular Audience Research

Service in the Czech Republic, ing. Josef Ehrlich was

originally inspired by British experience. During World War II

ing. Ehrlich was

in London. He listened to a speech about BBC audience research

delivered by Mr. Silvey in a London air-raid shelter during 2nd

WW Luftwaffe raids. He was so enthusiastic about the method

that the first thing he did after returning home in May 1945

was to set up a small group of researchers at the Ministry of

Information and started

daily interviewing of radio listeners about yesterday’s

programs. I was lucky to find the summary of the daily

findings from 1945-1952 in the Czech Radio archives in small

Czech town Přerov nad Labem. As far as I know, Mr. Ehrlich’s

effort to map Czech radio audiences was terminated in 1952 and

he himself was persecuted and probably arrested, setting a

precedent. The

persecution based on dossiers and testimonials about your

loyalty which implied collective liability (in traditional

Russian village context “krugovaja poruka” of the pre-20th

century period), i.e., it included a ban on travelling abroad

for the whole family and even some remote relatives sometimes,

barring access to the university education even for your

children, setting limitations for your professional career and

your family members etc.

Still, I managed to write an article for a

special Journalist magazine “Sešity novináře” where I compared

the 1950s and 1980s periods. There I mentioned listeners’

abnegation of a Sunday ideological programme which had been

prepared and presented by a prominent representative of the

ruling class, Prof. Zdeněk Nejedlý. The censors allowed my

article to be published, having first corrected the critical

sentence about Nejedlý (although deceased at that time,

Nejedlý had been still used by the local propagandists as an

appealing role model).

The response to my article was lively. Among

others, I was contacted by the widow of Mr. Ehrlich, which was

very nice. However,

I fear that as a consequence of this publication, the book

with the audience research findings by Mr. Ehrlich was

probably destroyed or hidden, perhaps becoming a collateral

damage caused by my article. Those who researched the subject

later did not seem to have the direct access to the 1950s

audience research data any more. Radio was a mainstream medium

in those days and via audience data you could study the

population’s cultural preferences, their attitudes towards

various current affairs, events, personalities etc. Unfortunately

the audience data of the 1940's and 1950's are lost."

In 1967 or 1968, therefore after the Jiří Lederer

period, Czech Radio Audience research was taken over by Mrs.

Jarmila Votavová. Although

a high Communist party cadre, she was attracted to modern

research methods. She managed to recruit leading statistical

specialists to train her staff (such as Souček and Linhart),

she supported special linguistic, musicological and

journalistic studies (by Bozděch, Branžovský, Karbusický,

Kasan), she invited Lederer to help, she hired a psychologist

(Smitka, Štěpánek), she launched or supported a magazine Radio

Broadcasting in the World (editor A. Meissnerová) and

professional audience researchers (Karpatská, Ort, Cejp). Under the fresh

Russian occupation J. Votavová apparently was not able to

organize the 2nd GEAR meeting, which should had

taken place in Prague in August 1968. She probably was not at

all in charge of the event. Once Tony Fahy, thus GEAR

chairman, asked

me about Miloš Řehák and Josef Čamský, since they were GEAR

members in 1967-1969. I suppose they represented Czech

Television which probably had to take over the organization of

the GEAR meeting

in Prague 1968. The Czech media (Radio and TV) played a key

role in the resistance against the Soviet occupation.

Logically, during the reinstating of the Soviet regime most

employees were purged. Supposedly as many as 80% of the TV

workforce was fired or left themselves during the purge which

started in 1969. With high probability, both Mr. Řehák and

Čamský, the first Czechoslovak ex-GEAR members, were also

expelled from the TV, and they disappeared into some other

professional fields or emigrated as did other 150 TV

employees.

Mrs. Jarmila Votavová herself maintained to keep

her position as the Audience Research manager only a little

longer. In 1970 she, too was expelled by her Communist

ex-comrades to some manual work in a factory somewhere. The

Study Section, “Studijní oddělení” in Czech, as the Czech Radio

audience research unit was called, existed only until 1971,

when all its former personnel definitely left with one

exception—editor of the Radio Broadcasting in World

magazine. At that time, the Czech Radio Research Section was

founded and Mr. Hruška, who was appointed its manager, began

to recruit completely new staff from scratch.

A long time has passed and I forgot many details

of my stay in the Czech Radio, but I still remember the key

moment that made me to move to the Home Broadcasting Research

Section and to adopt the position of its head. Until then it was

managed by Mr. Hruška, who became famous by such episodes as

depicted by the following phone call to the Czech Radio (my

approximate quotation): “There is a man lying on the ground at

the terminus of tram number 6, he is completely drunk. He

claims to be your boss. So if it is true, please come and take

him away.”

The General Director of Czechoslovak Radio, PhDr.

Ján Riško, a close friend of Foreign Secretary Václav

Chňoupek, kept

work briefings and meetings which were called by a Latin

expression Collegium to

highlight the importance of such almost ministerial

gatherings. One

day in 1976, an item on the agenda happened to be ‘the current

state of the audience research in Czech Radio’. When there was

Mr. Hruška’s turn to deliver his summary, he stood up,

stammered with heavy articulation “Dear comrades”, and as he

waved his hand with aim to develop his point, he fell to the

ground. This boozy gravitation brought me the position of

manager of the 3rd line, as it used to be

called by organizers of the compulsive indoctrination courses,

May Day parades etc. who never forgot to send me special

reminder.

In 1984 at the time of the conference of the

IAMCR (International Association for Mass Communications

Research held that year in Prague) Graham Mytton, head of the

audience research section of the BBC external services visited

the Czech Radio. We met at the conference. He then came to see

me and mentioned GEAR and an upcoming Budapest meeting in

1987. I was keen to attend but at the same time skeptical

about a real possibility to get a permission to go. However,

the political climate started to change: the new managing

director, K.

Kvapil (1985-89)

was young and was not so cautious like the former director

Karel Hrabal, who already retired. So I travelled to Budapest

in 1987 and was very proud to speak some English and listen to

English of others. I

recall how Peter Menneer had fun with this and could not

believe that English is as rarely used in Czechoslovakia as I

claimed.

Still my formal GEAR membership had to be

recalled since there was no equivalent Eastern organization

under Soviet auspices. So, somebody kind, I think Tony Fahy,

sent a denying letter in the name of GEAR to the Czech Radio

Headquarters saying that my name appeared at the list of the

members by some typing error and thus saved me from possible

persecution.

.

My travel and stay at a later GEAR meeting in

Brussels in 1989 was paid for by the BBC, since otherwise,

director Kvapil would not allow me to go. Again, I must thank

for the generosity of my GEAR colleagues. I took a train from

the Brussels airport to the centre of the city. And I recall

one linguistic incident. The tickets were being paid directly

on the train. When conductor came up to me I asked for a

ticket worth of 95 Francs: ‘quatre vingt quinze’ in my

polished French. The

whole compartment full of Belgian travelers stopped whatever

they were doing. They were expecting the conductor’s reaction

as if they were watching some TV sitcom. His response was

immediate as if learned by practice: we are in Belgium. There

is no such number four times twenty and fifteen. What we say

is 95 (nonante cinq) . The whole compartment was apparently

satisfied with his replacement and everybody was amused.

I safely arrived at the centre of Brussels, but

without luggage that was sent off to Canada by some airport

mistake. I could not change into a formal suit for the

reception in the Town Hall organized for us by the mayor of

Brussels. Not knowing how serious my possible infraction of

the dressing code may be and what the Western European manners

were, I apologised at least to my GEAR colleagues. In a couple

of days, my luggage returned from its Canadian trip and Peter

Menneer checked with me on that. After my positive answer he

inspected my jeans and beige pullover and stated in his usual

manner: I see, apparently these are your formal clothes you

put on now!

In 1990 I visited my third GEAR meeting in Bern.

This time under quite different political situation in

Czechoslovakia, including a changed climate in the Czech

Radio. Just several months earlier I returned from my short

stay in Vienna Radio-Television, having met Peter Diem. I

travelled back by train from the Franz Josef Bahnhof station,

named after the late Austrian and also Czech emperor. I sat in

a completely empty compartment, except for one East German

lady, whom I have seen earlier at the platform as she was

kissing with great passion some young man, apparently

Austrian. She

could not have guessed that within less than a year the Iron

Curtain would go down and she would be able to meet him

freely. As the train moved, she moaned from time to time and

we communicated a bit, me in my approximate German. I wondered

how many people were sitting in the train and she also guessed

only a few. We

arrived at the Czech border and the train stopped. All of a

sudden, 4 submachine gunners stormed into our compartment and

ordered us to step out to the corridor. They inspected all

our pieces of luggage, all seats, racks and corners of the

compartment. Then they noisily left without any loot. I

anticipated that border would mean troubles, that is why I had

rather tossed the “Western” foreign newspapers to the trash

bin at the Franz Josef Bahnhof. Such innocent objects as

newspapers could be easily taken as ideological diversion by

some keen policeman and therefore qualified as an offense.

The young German lady looked at me a bit

accusingly since the humpty-dumpty soldiers were Czechs as I

was. Finally, a man without uniform—in a casual suit came in

and without looking into our passports he directly addressed

me: “So you came back, Mr. Doctor”. He stressed this Mister

instead of customary ‘comrade’ of those times to show me his

watchfulness and to terrify me a bit. And also to express

his pity, that I did not stay in a capitalist country and

apparently planned to continue to augment police labour.

Within several months the Communist regime

collapsed and all this absurd show was over, all these evil

characters gone. Sometimes I wonder what name would be the

most fitting for my character of that period. For sure we started to

act in a brand new play after November 1989: this time written

by much more friendly playwright than the Stalinist one.